Get the Lowdown on Sake...

Find out its History, What it is, How to drink it

And...

Should you Really eat it with Sushi?

Sushi and Sake just seem to me, to go together. They even kind of sound good together.

"Rolls off the tongue...", as some might say.

But in actuality do they really go together? Do they really complement one another?

And besides that, what the heck is "S a k e" anyway? Where did it come from? How is it made?

Is it more like a wine? Or is it more like a beer?

And if I do decide to try it, how do I drink it? What do I eat it with?

All very good questions that we will try to cover on this page.

But to do that, we have to begin. And what better place to do that than at the beginning...where it all began...

At "The Dawn...of Sake..."

A Cliff Notes History

There is no exact known origin for Sake in Japan, except that it was created around the same time that wet rice cultivation was introduced around 300 B.C.

The first recorded evidence of the use of alcohol in Japan was in an early ancient 3rd century Chinese text called the "Book of Wei". In it they mention the "Japanese drinking and dancing".

Koji Mold introduced to Sake Brewing

During the Asuka period (538-710 A.D), a milestone in brewing occurred when Koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) was incorporated into the brewing process which now consisted of rice, water and Koji mold.

Koji mold, however unimportant or insignificant its name may seem to imply, is actually a very important "silent partner" in the manufacture of many mainstay food items consumed even today in Japan.

Not only is it a very important ingredient in the production of Sake, but it is also used in the fermentation of soybeans and is used in the making of rice vinegar, miso, soy sauce and many other Japanese foodstuffs. All of them part of the core Japanese diet.

It was so important that Dr. Eiji Ichishima of Tohoku University called the kōji fungus a "national fungus" (kokkin) in the journal of the Brewing Society of Japan. This recommendation was approved and made official at the society's annual meeting in 2006.

This introduction of Koji mold into the process was the beginning of what is today considered the origins of "true sake" (rice, water, Koji mold) and was the dominant alcohol during the Asuka period, but it had very low potency. Toward the end of this period, it is mentioned many times in the Kojiki (Japans first written history), which was assembled around 711-712 A.D.

Production moves to the Temples and Shrines

During the Heian period (794-1185) sake was controlled mostly by the government and was used during festivals and religious ceremonies. But around the 10th century and continuing on for the next 500 years, it began to be made by the temples and shrines.

In the Tamon-in diary, written by abbots from 1478 to 1618, they recorded many details about brewing in the Tamon temple. The diary even covered pasteurization (300 years before Louis Pasteur was even born) and the process for adding ingredients to the 3 main fermentation mash stages.

Breweries skyrocket during the Meiji Period

The period between 1868 and 1912 were know as the Meiji Restoration. It was a chain of events that restored imperial rule back to Japan under Emperor Meiji.

During this time, laws were written that basically allowed anybody with money to open their own brewery. Within a year, over 30,000 breweries opened in Japan. This run was short-lived however, as the government began to tax the industry more and more until all but 8,000 breweries were still open.

WWII reduces Production and Quality also goes down

Rice shortages during WWII caused the government to reduce the amount of rice that could be used for brewing. And it was also because of this restriction that it began to be produced where larger and larger amounts of pure alcohol and glucose were added to the rice mash, increasing yields but also reducing quality.

In some cases, breweries produced sake that had no rice in it at all. Needless to say, the quality varied greatly during this period.

Where the Tradition of Drinking Sake warm came from

It was also during this period that it started to be consumed warmed. The Japanese found that by warming the lower quality variety, it became more drinkable.

Of course, today it is more a part of tradition rather than being done out of the need to cover up poor taste, but even most Japanese don't know that that is the reason why they sometimes drink it warm.

And as a final note on the subject, the good quality varieties should be consumed chilled or at least room temperature as heating it removes some of the finer flavors.

Consumption peaks in 1974 and then starts to slowly decline

After the war, breweries started to recover and slowly began to increase their quality again.

But as the quality continued to increase, its overall consumption started to fall mainly due to competition from beer, wine and other alcoholic beverages. And it was during the 1960's that beer actually surpassed sake consumption for the first time.

Sake and its Future

From its peak of 30,000 breweries during the Meiiji period (1868-1912) to roughly just 1,100 active breweries today, the future seems quite bleak when seen from that light.

But because of the increase in the premium variety production coupled with a new interest from the U.S. (evidenced by recent double-digit year over year import numbers), it looks to be gaining a second wind and is here to stay for the foreseable future.

What is it and How is it Brewed?

Honestly, I've thought about how to best explain this, but no matter what I came up with, it seemed like it was going be a slippery slope.

My goal was to try to explain it so that you could come away with an idea of what sake is and also maybe what you might like or what you might want to try but it kept coming back to feeling like another study of wine...enlightening, but also sometimes confusing and somewhat convoluted.

I know many people who have been connoisseurs of wine their whole life and they still feel like they don't know anything...I know I don't.

But with that perspective in mind, I began thinking that maybe the best way to approach this might be to first break it down into its physical elements and tie that into how that relates to the flavor aspects.

Then, building on that, add in how different variables in brewing affect flavor like adding in brewer's alcohol, or the percentage the rice has been milled, etc., etc., and you should have a good foundation in which to start.

This knowledge in combination will help you understand what makes different varieties drier, sweeter, more delicate, smoother, fuller, etc.,

So with that direction, let's get started.

The elements are:

Rice, Water, Koji and Yeast.

Rice

The rice used to make sake is not the same rice that Japanese people eat everyday on their tables. This rice or Sakamai or Shuzo Kotekimai

has a rice grain that is larger and a starch content that is higher and

more concentrated than ordinary rice. It also contains less proteins

and lipids. It actually is not really that good to

eat.

The starch portion of the rice is called Shinpaku and is probably the most important single component in determining the quality of the product that will be brewed.

Basically you can look at it this way. Sake can be brewed from rice that has:

- Very little milled at all (little polishing away of the exterior of the grain of

the rice to expose more of the starch --- generally above 70% of the grain remaining but there is no requirement). This will produce ordinary,

everyday table sake similar to a table wine and is the majority

of the sake produced (about 80%).

- Has been milled (outer proteins and fats are polished away to increasingly expose more of the pure central starch core) (about 20% of what is produced). Typically milling is "down" to 70%, 60%, or even 50% or less of its original size. So if a rice is not milled at all (100%) it will make the cheaper, ordinary table variety, whereas the 50% milled is the most premium and expensive variety.

Study the chart below. It is a very good representation of, starting from the top, the best (most milled) premium classes (daiginjo) all the way down to the basically ordinary table class (futsu-shu).

And generally speaking, the more milled or refined or polished a rice is (50% being the most), the more delicate or smooth the taste will be.

Ok. So you now know that in the chart above that Daiginjo is the top of the line premium class.

But I guess you are wondering what the "distilled alcohol" addition is in the left hand column.

Let's look at that in a moment.

First lets talk about "Junmai-shu" or the right hand column.

The one that says "Rice, Koji, Water, and Yeast". This is the one that is considered the "pure rice" variety. It contains only the 4 necessary elements. No Brewer's or distilled alcohol is added.

Many brewers who make this type are proud of the purity of their product, and are glad it is not "contaminated" with distilled alcohol.

Junmai-Shu is said to have a "heavy, full and rich body", with a stronger rice influenced flavor and higher acidic level than most other premium types. Its fragrance is also said to not be as prominent.

Now let's talk about "Aru-ten" or the left hand column.

This is the other school of thought. The one that adds distilled alcohol during critical points in the brewing process.

So why would you want to do this?

Well, those in this camp say that doing so produces a more flavorful and fragrant sake. This is because the brewer's alcohol is added before the "mash" is pressed after fermentation, which extracts those flavors from the solids.

Deciding which you like better will be something you will have to figure out based on your taste preferences.

Water

As you can probably imagine, water is also a very important part of the process.

Not only is it used in almost every stage of the production from washing the rice to diluting the final product, it affects the final taste of the product dramatically.

Although most brewers source their water from wells, some do get it from lakes and rivers while still a few just use filtered tap water.

The source is not nearly as important however as how hard or soft a water is.

A harder water, with more nutrient content, will cause the yeast to work faster and multiply which results in more sugar being turned into alcohol. This normally will result in a drier taste.

Conversely, a softer water usually produces a sweeter taste.

Koji and Yeast

Step 1 - Making Koji

Koji is the name that is given to the mixture of steamed rice that has been sprinkled with Aspergillus oryzae (a mold) and allowed to ferment for 5 to 7 days.

The role of the mold spores is to break down the starch molecules of the rice into simple sugars so that they can be broken down even more by the yeast in the next step of the process.

When this step is completed, the Koji will have the smell of roasted chestnuts and will have a somewhat frosted exterior.

Making the Koji is the first step of the brewing process.

Step 2 - Making Yeast Starter (Moto)

Now in this next step, the Koji (left picture above) is mixed with steamed rice, yeast and water (right picture above) and allowed to sit anywhere from 7 to 14 days to generate the high concentration of yeast cells needed for fermentation.

Step 3 - Making Moromi

Over the next 4 days, the yeast starter is mixed with more steamed rice, water and Koji 3 separate times. This incremental approach allows the yeast to catch up with the increasing volume of Moromi.

So normally, it kind of goes like this.

- On Day 1 the yeast starter is mixed with more steamed rice, water and Koji.

- On Day 2 it is given a day to "rest".

- On Day 3, again more steamed rice, water and Koji are added.

- On Day 4 one last addition of steamed rice, water and Koji are added.

At the end of this process the size of the batch has effectively been tripled in size since it was started.

Step 4 - Aging the Moromi

At this point, the Moromi is allowed to sit in the tank and and ferment or "age" for 3-6 weeks.

Step 5 - Shibori (Pressing)

Assaku-ki Shibori (machine pressing)

At the end of the fermentation period, the mash is pressed or squeezed through a mesh to separate the solids from the liquids.

99% of all sake is pressed using a machine called an assaku-ki (picture above).

Here is where some brewers will add brewers alcohol to the mash before the pressing to extract the flavors and aromas that would otherwise be left behind in the solids.

In cheap varieties, a large amount of brewers alcohol may be added to increase volume.

The remaining 1% of may be pressed using a fune (long box) or Shizuku (allowed only to drip from bags).

Fune Shibori (Long Box Pressing)

This is a gentler, more traditional way of extracting the liquid from the mash or Moromi and generally produces a better quality product.

Basically, the it is extracted in 3 stages.

1st Stage

In the first stage, the moromi is poured into long cotton bags and one layer of bags is placed in the bottom of the fune. The 1st 3rd of the sake to drain out of the bag and come out of the drain in the fune is called arabashiri or “first run”.

2nd Stage

In this stage the bags are piled on top of each other which exerts a little pressure on the second 3rd of the extraction. This one is called nakadori and is usually considered the best quality for this type pressing.

3rd Stage

The final 3rd is extracted by taking a lid and putting it on top of the bags and exerting a little pressure on them. This pressing is called the Seme.

Shizuku Shibori (Drip Pressing)

This method supposedly produces the best sake as no pressure at all is used. The long bags filled are filled with moromi, hung and allowed to drip. This is the most time intensive way to press, even though no pressing is actually involved.

Step 6 - Pasteurization, Aging and Bottling

Normally, after pressing most sake is filtered, pasteurized and then aged for 6 months.

Then after aging, it is diluted with water to lower the alcohol content (which is usually around 20%) before it is bottled.

So is Sake more like Beer or Wine?

That seems to be the age old question, doesn't it?

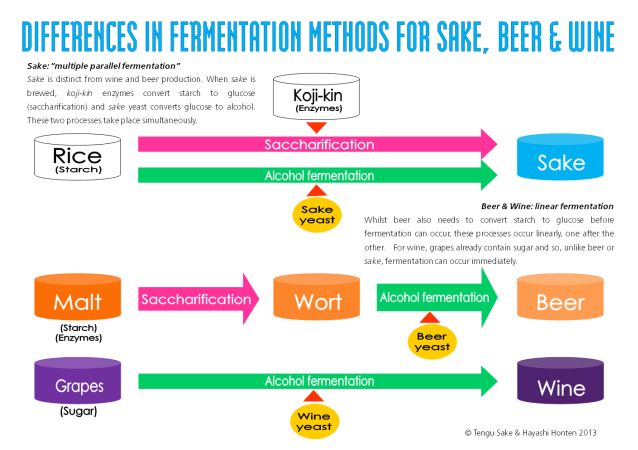

Well, in all honesty depending on what you are talking about, it is like both. Take a look at the chart above.

From a brewing standpoint, it is similar to beer in that the starch (rice for sake and normally malt for beer) is converted to glucose or sugar before being turned into alcohol during fermentation.

Wine skips this starch to sugar step because fruit juices are essentially already sugar so wine can go straight to fermentation.

For sake this is done by adding Koji-kin or Aspergillus oryzae (a mold) to steamed rice.

For beer, when the malt (usually barley that has been partially germinated and then slowly dried in a kiln so as to not disturb the enzymes in the grain) is added to hot water during the "mashing" process the naturally occurring enzyme in the grain converts the starch to glucose.

And for beer, this "saccarification" results in a 1st step liquid referred to as "Wort".

For Sake, the Koji is mixed with steamed rice, yeast and water continuing the "saccarification" process and simultaneously starting the alcohol fermentation process at the same time. The resultant mixture is what is pressed.

The beer "Wort", moves on to another tank called a "copper" or "kettle" where it is mixed with hops, etc., then to "whirlpool" to separate out solid particles and then a heat exchanger to cool it down before ending up in a fermentation tank where the yeast is finally added. This is the 2nd stage type process done in beer that is done all together in the making of sake.

Which is what makes the beer and sake brewing process different. But they both are brewed. Which give them that similarity.

So O.K. Let's recap.

Beer and sake are similar because they both use grains that have to be converted to glucose or sugar before they are fermented (whereas wine is made from fruit and can go straight to fermentation) but they are different during fermentation because sake fermentation occurs simultaneously along with saccharification in 1 step whereas beer fermentation occurs only after saccharification making it essentially 2 steps.

So what about wine you say?

Well first, the definition of wine is "an alcoholic drink made from the fermented juice of a fruit, such as grapes".

And rice is not a fruit and is incapable of making any kind of juice. So when you hear of sake being referred to as "rice wine", that is totally inaccurate. It can't be a wine.

But here's the other side of this weird coin. It is drunk more like a wine. It is normally best served chilled, sometimes even in wine glasses, and especially if it is a premium sake like some wines are.

And it has tastes and flavors and nuances that are more accurately compared to wines rather than beer.

So from a selection, tasting, and consumption standpoint sake is more like a wine.

Totally confused? Good!

Let's figure out how to go and pick you out something to drink!

How to make your Pick

Well, I guess you figured out by now that all of previous stuff we just trudged through, was leading up to something...well, Yeah!

Drinking!!!

Ok. Getting ahead of myself here. I guess we gotta pick out something to drink first, don't we :-)

You know, this is going to be kinda like picking out a wine. Hit and miss. Yeah, bummer.

But I think by looking back on the some of the previous info on this page we might can narrow down what you might tend to like by comparing it to what you like in a wine.

If you don't drink wine, well...uhhh...I can't help ya.

Just kidding.

Here's the handy dandy classification chart again to reference while we're talking.

Pick a "Ginjo"

I think I'm going to hit this one hard and fast and make a recommendation right off the bat.

If you are new to drinking sake, either have not had it before or have had it (maybe some cheap heated up stuff at a sushi restaurant... sound familiar?) but maybe it didn't taste as good as you had hoped it would (ok, maybe it even tasted kind of like crap...)

Or maybe you have tried it before but don't feel like you know what you are doing or have no sense of direction...

Then this suggestion is for you. Look at the chart above.

When you go to the liquor store:

- Look only at the sake that has "ginjo" in the name or on the bottle. If you do nothing else, do that. That by itself will probably get you into the top 10 - 15 % of all the varieties made. Pretty good for your first shot at it, huh?

- If you don't mind spending a little more money, and want to start out with a top of the line pick, then select one with "diaginjo" somewhere on the bottle.

Picking one with diaginjo or ginjo on the bottle will be the single best thing you can do to give sake a fair shot at impressing you.

This will be the best of the premium varieties.

So. To keep it simple, if you remember nothing else, remember that.

Pick a "Ginjo".

Narrowing down your "Ginjo" - Do you like your's Junmai? or not?

So you've decided to go "Ginjo".

Maybe you've already tried one or two and want to up your game by adding some focus, or maybe you've yet to pick one out but you want to have some kind of purpose and method to your selection instead of it being all madness.

Either way, a good way to start off might be to pick a "type" that you think may be most appropriate for you and focus on that.

For instance. Maybe money is no object and you want to try the best.

So start off by trying one within the Daiginjo class (where the rice has been milled at least 50%). Try both Daiginjo (distilled alcohol added) and Junmai Daiginjo (no distilled alcohol added). Pick one of each from the same brewer (if they make both) and compare. See which you like better.

The Daiginjo should tend to be light, refined, delicate, maybe complex and have nice aromatics. Some might say a little more well rounded because the alcohol extracts other flavors and aromatics from the moromi.

The Junmai Daiginjo should also be light and refined and delicate also but maybe a little fuller with a stronger rice influenced flavor. A little more acidic.

Taste is relative. In the end, what you like is what you should drink. There is no right and wrong.

Now, if you don't have the pocket book for Daiginjo, then do the same thing stated above but drop down to Ginjo.

In the end, hopefully this exercise will help you determine generally whether you prefer your's Junmai or not.

What if I want to try something that has some of the same flavor notes as my favorite wine?

Well, there may be some things to look for to help you accomplish that.

Regardless of where your focus is on the chart, whether you are hitting the diaginjo, or just ginjo or junmai or honjozo the following should apply.

We will focus on finding something either sweeter or drier because that seems to be a major common point of preference for most wine people. Some people drink both...but MOST people prefer either dry or sweet or at least something that leans more toward drier or sweeter.

So, let's see if we can try to determine that when we go shopping.

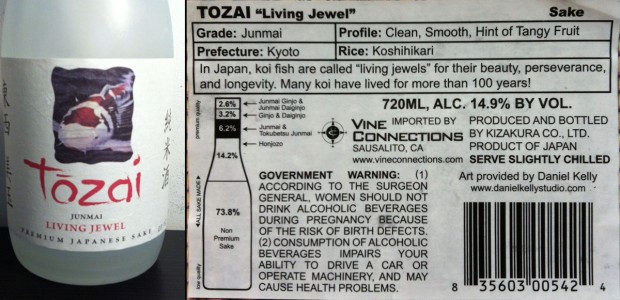

Some labels will have helpful info already on them. You can see this one is a "Junmai" (if you been paying attention, you already know what that is :-)

Above is another one. A Junmai Ginjo.

Nihonshu-do or SMV (Sake Meter Value)

This can often be found on the bottle and is a general indicator of dryer versus sweeter. Normally the range is in the -5 to +15 range with -5 being the sweetest and +15 being the driest.

A good way to remember how to use this scale as a reference is, "Higher is drier".

Other terms to look for:

- Karakuchi - Dry

- Amakuchi - Sweet

- Tanrei - Light and refined

- Omoi - Heavy

These terms can be used in combination also. As an example, tanrei karakuchi is both light and dry.

So what do you do with Futsu-shu?

Everything up to now has been focused above this class. This is the "working" class stuff. The table variety. 80% of all the sake made falls in this range.

And its not bad per se. You can drink it. But you want to know what I really like to do with it?

I like to cook with it. I keep a bottle of Gekkeikan around all the time to cook with. If a recipe asks for wine, I consider using this.

This is kind of a secret that I'll let you in on. This is the secret ingredient I use in my spaghetti sauce. Believe it or not, it leaves a beautifully smooth, slightly sweet after taste that I cannot get with anything else.

It is really nice in almost any tomato dish. Lasagna sauce? Yep. Stew? Uh, huh. Its great. Give it a try.

Its also good in marinades too. Try it in your homemade teriyaki sauce.

Any recipe that calls for or you would use wine in, try using sake. You won't be disappointed.

And finally, I might heat some and drink it. If I don't have a nice cool diaginjo to sip on, or I feel like drinking some warm sake, I might heat up some Gekkeikan. Its actually kind of nice sometimes for a change.

How to Drink your Sake

Wow. I can't believe we are actually bringing this discussion to a close.

We've learned some history, found out how it's made, looked at whether its more like beer or wine, picked some out...and now...we are

...F I N A L L Y...

Ready to Drink some!!!

What to drink Cold

Generally, the premium variety is meant to be consumed "chilled". This would include anything with "Ginjo" in the name.

Cool (59°F, like white wine)

Chilled (50°F)

Cold (41°F)

Most refrigerators are recommended to be set between 35 and 38 degrees; so based on that, you may need to let your bottle set out at room temperature for about 15 minutes before pouring to get it in and around the 50 degree range.

As for the vessel, I would recommend using a wine glass for premium chilled sake. You will be able to swirl and smell it if you'd like, similar to what you would do with a fine wine. The premium ones do have distinct, fruity, and aromatic notes similar to those of wines which a good wine glass should be able to make more prominent.

What to drink Warm

Robust and full-bodied ones like Honjozo and Junmai are best served warm---around body temperature (95-98 degrees). Futsu-shu should also be warmed.

Look at the picture below on the left. Those are 3 examples of vessels called "tokkuri". This is what you would put your sake in before you heat it and then serve it from afterwards.

In the middle we have a traditional sake cup. Notice the concentric circles in the bottom. That is used to determine clarity.

On the right, the wooden box is called a "masu". Originally, and for over 1300 years a masu was used to measure rice, but is now more commonly known to be used to serve sake.

Warm (95°F)

Hot (113°F)

Very Hot (more than 131°F, but not to be boiled)

To warm your sake:

- Fill a small pot about 1/2 full of water and heat to just near boiling. Turn off the heat.

- Place the tokkuri filled with sake in the water.

- Allow to sit between 3-5 minutes or until the sake is around 98 degrees (this will vary based on the starting temperature of the sake)

- You can pick up the tokkuri and use your finger to feel the depression under the bottom of it to gauge what the temperature of the sake is. With a little experience you will be able to quickly gauge the perfect drinking temperature.

How to Serve Sake

There are a few "rules" of etiquette when it comes to drinking your beverage. The main ones are:

- Never pour your own drink. It is considered impolite.

- Lift your glass or cup for your companion to fill and then fill your companions cup.

If you remember the 2 rules above, and pour for your companion as in the pictures above, or allow your companion to fill your cup as seen in the pictures above, you will be well ahead of the game.

And not to split hairs here or anything, but the guy (or girl?) on the left is holding his cup more "properly" than the guy in the right picture because it is better to hold your cup with one hand around the cup and the other hand under the cup.

Just sayin'...

What to Eat with your Sake

Should you drink Sake while eating your Sushi?

The quick, "proper" answer is No.

The reason that most feel this is not really proper is that since sake is made from rice and sushi is essentially anything served with sushi rice then the flavors of the two together are more redundant or tend to conflict rather than complement each other.

Now, if you don't care, or don't agree or you just freakin' like sake with your sushi, then I say "Go for it!".

It really does boil down to what you like.

Drink Sake with Sashimi

This is where it is the most appropriate or even encouraged.

Sashimi is not sushi. Rather it is just the meat with no sushi rice.

Usually served with daikon (shredded japanese white radish) and normally it is the first thing you will order and eat before ordering your sushi.

For more on this visit eating your sushi or read my article on this subject on ezinearticles.

Try Sake with meals you would normally order Wine with

As you become more experienced with the different types and flavors, you will see that it does have a lot in common with wine and does tend to pair with food similar to the way that wine does.

You will definitely get some attention and seen as a ground breaker around your friends, family and co-workers when you go "non-traditional" and order a nice premium sake with your filet instead of a Pinot Noir or Cabernet Savignon.

Wouldn't it be cool if you could open up this new, unconventional, and virtually unknown aspect of drink and food pairing to others?

In Closing...

On that note, I'd like to end this by thanking you for sticking with me to the end of this very long page on Sake.

I hope you enjoyed it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

If you are wanting to continue your education on this subject, then I'd like to recommend you head on over to Sake World. My friend John Gauntner is one of the foremost experts in the world.

If anybody's got the answers to your questions, John does.

Like this Page?

|

|

Follow me on Pinterest

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.